Why Worry about Freight?

While passenger trains and rail transit are where most public interest seems to lie, freight trains are where most public benefit lies. The old iceberg analogy seems apt. The highly visible part that most people think of when they hear “iceberg” corresponds to passenger rail. The much larger part, however, lying submerged below the water line, and unseen by most people, is freight rail. Very simply put, because freight rail moves so much more tonnage and volume than is the case with passenger rail today, the potential for savings deriving from Steel Interstate efficiencies is also much greater for freight. Fortunately we don’t have to choose one or the other. We can have the appeal of passenger rail and the enormous benefits of freight rail, because both can be handled on the Steel Interstate.

Because of a steady decline in rail capacity, and an ongoing growth in rail traffic, the nation’s railroads are near capacity [link to section II d, above]. Though this has temporarily been alleviated somewhat by the economic downturn, the current up-tick in industrial production has led recently to strong year-over-year increases in rail car loadings. So capacity constraints are likely to reemerge on North American rail lines when a recovery is underway. The Steel Interstate System can provide a sustainable national infrastructure initiative to address rail capacity constraints for many years to come and create the super-railroads we need for the remaining decades of the Twenty-first Century.

Benefits

The chief benefit from concentrating freight flows on the Steel Interstate is the capability to move from oil-powered highway transportation to electric powered rail transportation. Substitution of domestically-generated electricity can liberate our national transportation system from oil. Not only is this beneficial from a national preparedness standpoint for a time when oil may no longer be abundant or affordable as a transportation fuel, but it, more than any other single program, furthers goals of energy independence [links to Peak Oil and National Security].

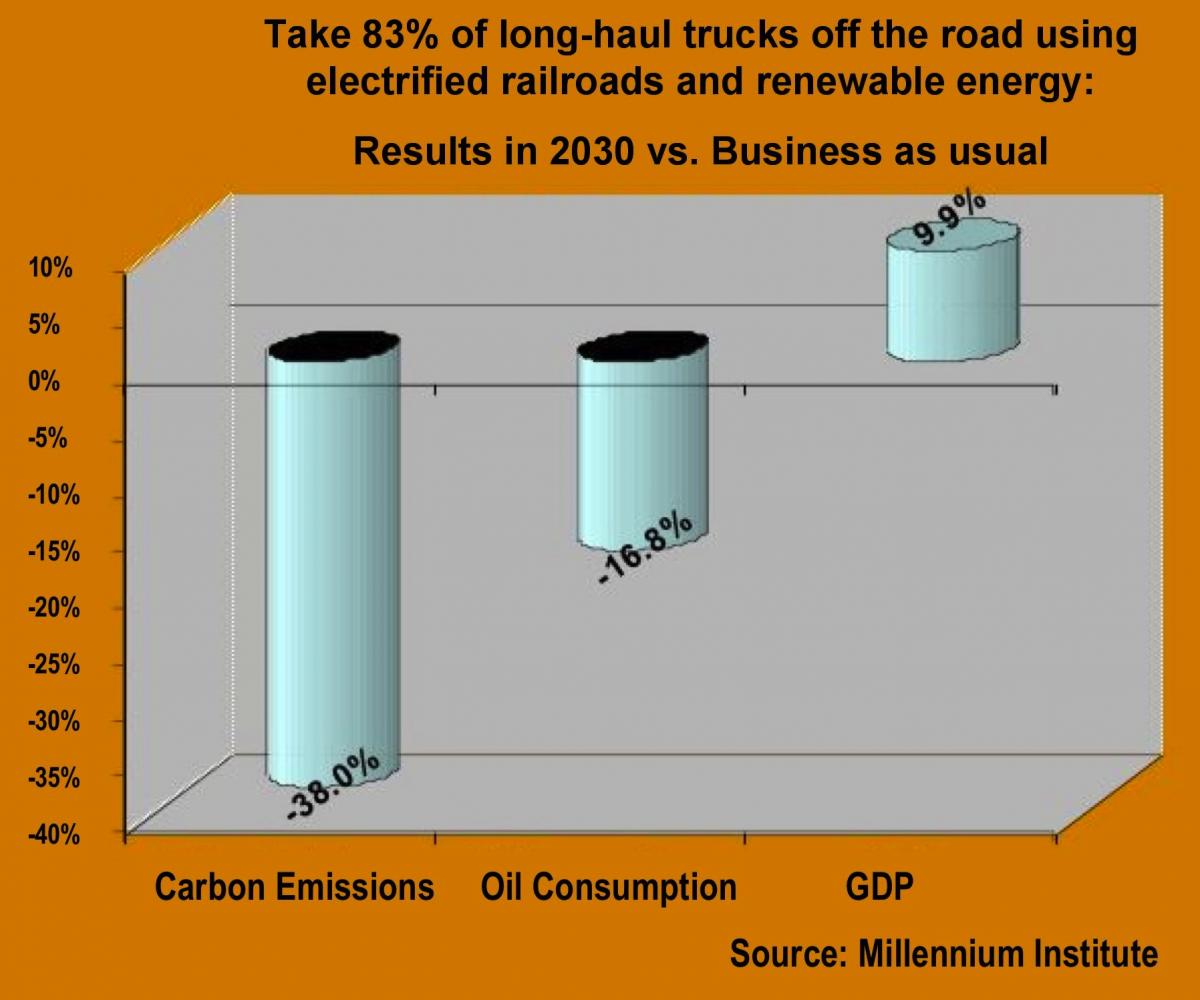

Independent petroleum researcher Alan Drake, in a collaborative study with the Millennium Institute and in articles published in the on-line journal Oil Drum, has shown the clear potential to save oil by moving land transportation of freight to more efficient, electrified rail.

Electrifying 36,000 miles of US railroads could take as little as six years with “Maximum Commercial Urgency” according to Appendix Two of the Oil Drum article. The Russians electrified the Trans-Siberian Railroad in 2002 and to the Arctic port of Murmansk in 2005. The Chinese are engaged in a massive program of electric rail line construction, and railroads throughout Europe are electrified. In 1996 Amtrak embarked a major project to extend electrification 157 miles from New Haven to Boston to complete its Northeast Corridor line. So there are no technical obstacles to electrifying railroads.

Drake calculated that switching current rail freight from diesel power to electric propulsion would save 185,000 barrels of oil/day because of the greater efficiency of electric locomotives. However this seriously underestimates the fuel saving potential, especially in an oil constrained future, because the real benefit accrues from diverting freight from the highway to rail. Transferring just 8% of the truck ton-miles to electrified rail would save another 204,000 barrel/day. Transferring half would save 1,276,000 barrels/day, plus the 185,000 barrels/day for 1,461,000 barrels/day. Transferring 85% of truck freight to rail, and electrifying half of US railroads, which Drake considers to be possible with a large enough investment ( Appendix Four of the Oil Drum article), would save 2.3 to 2.4 million barrels/day. That is 12% of USA oil used today for all purposes, not just transportation.

This potential dwarfs oil savings projected from all other energy conservation and energy independence campaigns being waged in the U.S. Best yet, no new technology is required. This analysis shows that the major oil savings lie in transferring freight from trucks to electrified rail. Electrified rail passenger service is an added, but unspecified, bonus.

This potential dwarfs oil savings projected from all other energy conservation and energy independence campaigns being waged in the U.S. Best yet, no new technology is required. This analysis shows that the major oil savings lie in transferring freight from trucks to electrified rail. Electrified rail passenger service is an added, but unspecified, bonus.

Extrapolating back to 60% of truck traffic diverted to rail from his 85% figure would yield an 8.47% reduction in U.S. petroleum consumption. Because skeptics question whether 85% would ever be possible to divert, RAIL Solution has used a more conservative 50% of trucking to try to account for short distance trucking that can't be diverted. That would result in a 7% reduction in the nation’s total oil use. And at only a 1% increase in electrical use nationwide, most of which should be capable of being supplied through conservation or use of renewables.

Whether the best target number is 50%, 60%, or even 85%, the Steel Interstate affords us the best hope to achieve it. Today’s rail system in North America lacks the capacity to divert significant amounts of additional truck-hauled freight to rail. Drake introduces to this dialogue the “Pareto Principle”, which holds that the best 20% of the system will produce 80% of the work (traffic flow). This has been true with the Interstate Highways and no doubt would be true as well of the core national Steel Interstate network. Not only would important new capacity be added on the upgraded, expanded, electrified network, but freight carried there would be lured off the less efficient secondary lines, freeing up space there and in congested yards and terminals as well.

Freight Service Offerings

Bulk Commodities: Long unit trains of coal and grain are often what people think of when one mentions railroad freight. Certainly such trains comprise a significant portion of the tons moved by today’s railroads. This would not change under the Steel Interstate, with the possible exception that such trains would be shorter and faster to blend better with the other traffic mix. This freight is mostly on rail already, will stay on rail, and there is little likelihood of diverting much more from highways. The economies of moving large volumes long distances simply prefer rail, and truck moves of bulk commodities tend to be short movements into grain elevators, barge terminals, or coal preparation plants.

Mixed Freight: This type of train is still quite prevalent on the nation’s rail lines. It consists of a mix of boxcars, tank cars, covered hopper cars, multi-levels, and gondola cars carrying a large variety of raw materials and manufactured goods. Much boxcar traffic has shifted to intermodal containers in recent years, but general freight such as lumber, steel, chemicals, ethanol, and new automobiles are still common on mixed freights. The future for mixed freight on rail is also a mixed bag. High value, time-sensatitive goods will continue to shift to containerization for secure handling and higher speed. But there is also a potential through faster, more reliable rail service on the Steel Interstate to attract more of this freight moving by trucks over the highway, especially over mid- to long-distances where rail economics will be most compelling, especially in an environment of high oil prices.

Double-stack Containers: This is the primary competitive weapon of the nation’s railroads today in competing for truck freight. The concept was born at ports, where the rail carriers provided a critical shipping leg for movement of goods inland once containers were unloaded from oceangoing ships, and also from throughout the country to the ports for export.

Cranes transfer cargo between ships and double stack trains at the Panama City port.

Now the railroads are focusing strongly on applying the double-stack concept for movements within the continental U.S. not involving ports. This is called “domestic containerization” and is being developed primarily between the Class I rail carriers and their major trucking customers, such as Schneider, Swift, J.B. Hunt, and UPS. These large truckers have sophisticated linear program models to determine the best way to move a shipment to destination. Sometimes economics favor rail instead of over-the-road haulage. This can arise from driver shortages, out of balance freight flows, proximity to rail intermodal terminals, and other such variables. These major truckers are investing in specialized containers to build in this flexibility in their routing algorithms.

Double-stack intermodal freight has been a growth market for the nations railroads, and domestic containerization has complemented the service offerings. However, these conventional intermodal trains are long and relatively slow, approximating at times the characteristics of bulk commodity trains. Double-stack intermodal terminals are huge, often occupying hundreds of acres, and rely chiefly on overhead cranes to lift the containers into railcars. Known as “well” cars, these specially designed cars have a low profile where the bottom container sits down between the wheels to permit room to stack another one on top. Moving containers through today’s massive rail intermodal terminals is often not easy or quick. Containers often need to be handled several times, and encounter cost and delay, especially where direct transfer between truck and train is not possible and the container needs to be stored in the interim.

The cost and delay inherent in such terminals limits the competitiveness of rail versus truck haul on the Interstate Highway system. A truck needs to haul the container to and from the rail facility, and can easily drive the full trip from origin to destination and cut the railroad out of the haul altogether. Because of the need to recoup or amortize the terminal cost and delay, rail is most competitive on the longest distance hauls, where truckers would have to stop two nights en route for mandated rest. Thus rail market shares between the West Coast and the Mid-West tend to be high – often 90% or more. Between the East Coast and the Mid-West where a competing trucker could only need to stop one night, rail is less competitive and market shares in the 50 – 60% range are more common. Under a thousand miles it is hard for the conventional double-stack intermodal model to be competitive with over-the-road trucking. These are all rules of thumb to help understand the economics at play; there are always exceptions.

A BNSF double-stack train westbound at Belén, New Mexico, May, 2010. Western railroad lines often feature such trains in each direction multiple times each hour around the clock.

Open Intermodal

If railroads are ever to handle 50% or more of the truck freight now moving on the highways, a greater variety of services will be necessary. An intermodal model is needed that can carry not only containers but trailers and whole trucks. Loading and unloading need to take place faster, at a wider choice of terminals, smaller and more compact in design. This kind of more nimble, streamlined service profile will be needed to lure trucks on distances under a thousand miles, especially independent truckers and fleet operators who have no interest in containerization.

Open intermodal can be the key to broadening the appeal of rail service so that diversion of 50% or more of the truck freight now on the highway becomes feasible. Railroads would have to add a huge number of additional trains to accomplish this. Now this is not possible because of capacity constraints on the system. Once alleviated through construction of the Steel Interstate, however, the U.S. can begin the serious work of moving a much higher percent of land-based freight by rail.

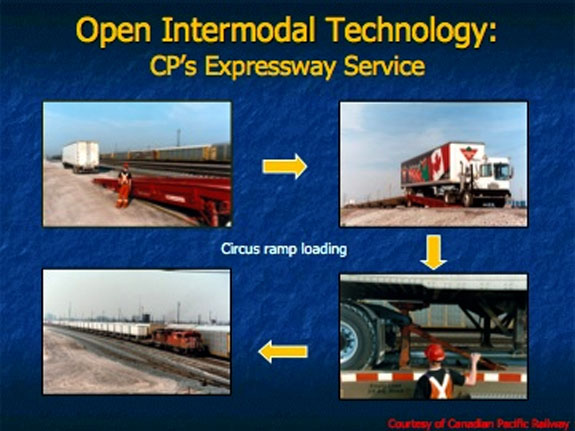

Currently the only open intermodal service being offered in North America is Expressway branded service offered by Canadian Pacific on its route among the cities of Montreal, Toronto, and Windsor/Detroit. There are multiple departures each day on each route, and the technology enables all trailers to be handled – tanks, flatbeds, bulk trailers, as well as any dry van trailer. This flexibility opens the rail option to a much greater population of possible users than the very few dry van trailers that can use crane-lifting transfer of conventional intermodal terminals.

Canadian Pacific offers an open technology intermodal service that can handle all kinds of trailers, not just the few dry vans that can be crane-lift transferred.

With the Expressway concept, truck trailers are backed onto strings of flatcars at terminals using a drayage tractor, and removed to the parking area in the same manner upon arrival at destination.

In Europe, in countries from Scandinavia to Turkey, but concentrated in the crossroads nations of Switzerland and Austria, an open intermodal concept is in increasingly widespread use. It goes by various names such as Roll on/Roll off, Rolling Highway, and Truck Ferry. But its unique feature is that entire trucks are handled on these trains. Drivers travel on the train as well, in passenger cars, and rejoin their trucks when unloading at destination. The full trucks move on and off the trains, consisting of a continuous platform of flatcars, driven by their own drivers. This type of handling is often referred to a “circus-style” loading, because circuses, as well as military convoys, have loaded like this for years.

Trucks roll off a Hupac rolling highway train at its Freiburg, Germany terminal.

A RAIL Solution account of a visit to a Hupac terminal at Freiburg, Germany, with photos, is available here.

This is not necessarily the type of operation best suited for American use, but it is significant in that a need for it was perceived and the equipment and service package custom designed and deployed in multiple markets. In the U.S. we would not need the highly-specific, low-profile car design needed to for European catenary clearances. And the accommodations for the drivers seem a bit on the primitive side.

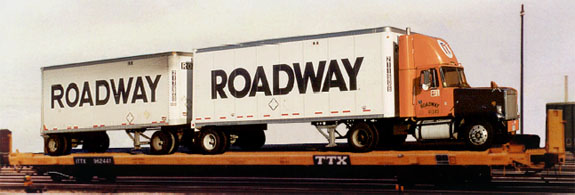

Here is a concept photo showing how a familiar American truck might appear when loaded on a truck ferry train. (Anderson & Associates)

If rail is to have any hope of diverting 50% or more of the truck freight currently on the nation’s highways, an open intermodal component will need to be part of the strategic service mix. It’s flexibility and ease of use can appeal to independent truckers driving over the road where containerization cannot. A recent Virginia study examined the trucks moving in the Interstate 81 Corridor. Conventional, double-stack intermodal service was determined to be able to divert 22% of the long distance, through trucks (13.3% of all trucks). But then in successive iterations, more open-intermodal features were added to the rail corridor. Ultimately a combination of strategies was envisaged that had the potential to divert 54.2% of the through trucks (37.7% of all trucks).

And another big advantage is that a trucker does not have to give up his business to the railroad, as is the case with conventional intermodal. The truckers retain all their existing business and accounts, continue to haul the same freight, but become in turn the railroads’ customers, riding aboard trains instead of driving all the way. If the open intermodal service can be structured to be truck-competitive in terms of speed, reliability, and cost, there is no reason a trucker would not want to use it. Being able to have the truck continue to move while the driver sleeps, represents a huge productivity improvement over having to stop and sleep at a truck stop or roadside rest area.

Currently the U.S. rail network lacks the capacity to offer such services that could be competitive in the three key areas indicated – speed, reliability, and cost. But the Steel Interstate can change that. The Virginia study used an annual truck count on I-81 of about 3.4 million (a reduction from the pre-recession number closer to 5 million). Roughly 60% of the trucks are long haul trucks passing through Virginia. That number is just over 2 million. If they were spread evenly over the year, and all diverted to rail, trains would have to handle 5,570 trucks per day. If half moved each way, almost 2,800 trucks would be moving in each direction. If they were moved on relatively short, fast trains of 35 cars each, about 80 trains each day would be needed in each direction on this line. This is over three per hour, or less than 20 minutes between trains both ways.

Frequency data on the I-81 truck flows show sharp peaks northbound and smaller ones southbound, so the flow would not be smooth across the days of the week and hours of the day. At times a train would be needed every 10 minutes to meet peak demand. This illustrates the rigorous infrastructure requirements a railroad would need to be able to offer this kind of truck-competitive service. Today there is a single-track Norfolk Southern line paralleling I-81 between Knoxville, TN and Harrisburg, PA. There is other freight on the line today. So it is easy to see that an open intermodal service with the requisite speed, reliability, and cost could not happen there today. But once the line were upgraded to Steel Interstate standards, this frequency of truck trains could be supported, along with passenger trains, mixed freight, conventional intermodal, and occasional coal trains. Such is the challenge and promise of the Steel Interstate.

Hurdles

Financing is the most obvious barrier to national implementation of the Steel Interstate. Even though, as infrastructure projects go, the SIS is unique in being able to generate sufficient savings to pay for itself, seed money is necessary to get started. Railroads in North America are largely privately owned. Many have annual capital budgets in excess of a billion dollars. These funds are invested routinely to make improvements to each company’s system. The funds are allocated to projects across each railroad in such as way as to maximize rate of return, which makes sense for shareholder-owned enterprises.

The more or less 35,000-mile Steel Interstate network would cost hundreds of billions of dollars, well beyond the capability of the private companies to fund. Thus, just as the federal government assisted with the early Western expansion of the railroads as a national prerequisite for growth and expansion, it needs to fund the Steel Interstate as a prerequisite to energy independence and preservation of national mobility in a post-Peak Oil world. The investment would have most immediate benefit if rolled out under a program a maximum urgency, but a sustainable effort transcending many decades, like the Interstate Highway program, seems more likely.

In order to attract the necessary federal support, more people in key decision-making roles need to understand and appreciate the manifold benefits the Steel Interstate can offer to the nation. That is the genesis of the North American Steel Interstate Coalition. Pulling together we can be more effective and a stronger educational voice than any single group or individual can be lobbying elected representatives separately. Our hope is to influence recognition and funding of the SIS concept in upcoming federal Transportation Act reauthorization efforts. Public opinion is favorable. More emphasis all the time is being focused on balanced transportation funding, not just more highways as the answer to every problem of congestion and growth. Public transit, greenways, bike lanes, and even safer sidewalks and other pedestrian projects are vying for funding as public opinion moves more strongly in the direction of reduced dependency on cars and oil.

A second identifiable hurdle is relationships and negotiations with the Class I railroads of North America. These private companies hold the rights-of-way that will be needed and utilized for most of the Steel Interstate. While they will benefit from a vastly upgraded core network of rail lines, these companies can be expected to resist efforts to bring government funding into a private business.

At times the public may view this as inappropriate as well, so a solid case needs to be made that public benefit of such involvement exceeds public cost, and this is not just a subsidy to enrich the railroad companies.

Railroads have become gradually more accepting of public/private cooperation in rail improvement projects in recent years. Perhaps these Steel Interstate corridors can be structured in this same way. The railroads would get credit for bringing all their current assets to bear on the project, and the public would bring new money. Some kind of joint ownership and operation would result. The railroads will want to safeguard their franchise rights on their lines, and the public will want to be sure the Steel Interstate routes get the widest possible use. Conflicts could result from these possibly antithetical objectives, and difficult negotiations may be needed to develop an acceptable template for Steel Interstate projects.

See the full concept page or more information on passenger service.