Why do we need a national rail system for the Twenty-first Century with more speed, reliability, and capacity?

Glancing back in time to see how we got to where we are with transportation helps bring imperatives for action into clear focus.

The railroad industry’s capacity has been in steady decline. The interstate highway network diverted large amounts of freight, especially time-sensitive and high-value products, away from the railroads and onto the highways. The railroads responded by abandoning thousands of miles of light density lines, taking up double-track on many routes, removing sidings, scrapping freight cars, and otherwise implementing widespread downward capacity adjustments. In addition to declining business, the steady impact of paying property taxes on every mile of track and piece of rolling stock provided a further inducement to downsize wherever possible.

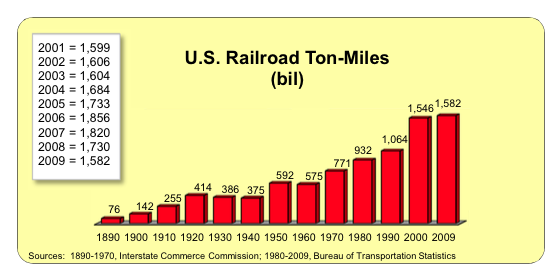

As this downsizing slowed, the rail industry was unexpectedly hit by traffic growth. U.S. railroad ton-miles have tripled in the period from 1950 to 2009:

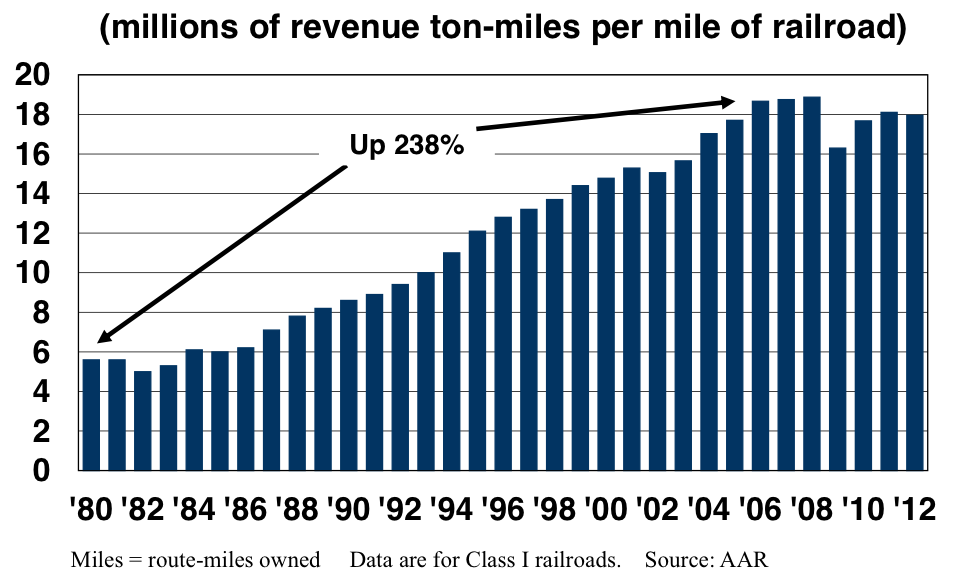

This effect of rising traffic levels and shrinking infrastructure can be seen most dramatically when one is divided by the other to produce a “ton-miles per mile of road operated” statistic for the industry. In the table below, data for a 33-year period (focusing before the Great Recession) show that revenue ton-miles per mile of railroad increased by 238%. With that much traffic moving on a shrunken rail network, no wonder bottlenecks are increasingly prevalent.

All indications portend that this rising traffic trend will continue now that the economic recovery is boosting rail car loadings, which area function of industrial activity and increased imports of goods from Asia. The Steel Interstate will equip the nation with a super-railroad level of infrastructure, just as the Interstate Highway System did for roads in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, providing vitally needed new capacity and allowing rail's share of freight movement to grow.

The plan for shifting mobility responsibilities back to the rail mode now relies more on upgrading the rail network we have instead of adding substantially more route miles to that network. Former FRA Administrator Gil Carmichael described this system in 1999 as "Interstate II." [Ref. 1, 2] Subsequently, the Department of Defense mapped out its 38,000-mile Strategic Rail Core Network (STRACNET) [Ref], which is the starting point for conceptualizing the North American Steel Interstate System.

Here is what can be achieved: Dedicated trains of trailers will outperform trucks. The model for this high-performance, higher-speed rail network borrows from a study conducted for Virginia (Reebie Associates, March 31, 2004— “Northeast-Southeast-Midwest Corridor Paralleling I-81 & I-95 Marketing Study”), which listed design criteria including: reduced curvature, full double track with frequent crossovers and bi-directional signaling (now referred to as Positive Train Control). The Reebie study went on to say that intermodal trains need to travel at passenger train speeds to be truly competitive with—and to divert—over-the-road trucks.

Learn more about:

How Railroads Became Marginalized - A BRIEF HISTORY